Sleep we never had - Prof. A Roger Ekirch and the myth of

‘segmented sleep’

In his 2001 paper ‘Sleep We Have Lost: Pre-industrial Slumber in the British Isles’ Roger Ekirch claims that “Until

the close of the early modern era, Western Europeans on most evenings experienced two major intervals of sleep

bridged by up to an hour or more of quiet wakefulness“. He states that “The initial interval of slumber was usually

referred to as "first sleep,” and that “The succeeding interval of slumber was called "second" or "morning" sleep”. He

states that “Both phases lasted roughly the same length of time, with individuals waking sometime after midnight

before ultimately falling back to sleep”. He claims that this mode of sleeping was “the predominant pattern of sleep

before the Industrial Revolution” and that “consolidated sleep, such as we today experience, is unnatural”. And

states that “One remarkable implication of segmented sleep is that our pattern of seamless slumber for the past two

hundred years has been a surprisingly recent phenomenon, the product of modern culture, not the primeval past”.

Ekirch further developed his hypothesis in a second paper in 2015 and a letter to a scientific journal in 2016 (

o

Ekirch AR. Sleep we have lost: pre-industrial slumber in the British Isles. American Historical

Review. 2001 Apr 1;106(2):343-86.

o

Ekirch AR. The Modernization of Western Sleep: Or, Does Insomnia have a History?. Past &

Present. 2015 Feb 1;226(1):149-92.

o

Ekirch AR. Segmented Sleep in Preindustrial Societies. Sleep. 2016 Mar 1;39(3):715-6.

o

Ekirch AR. What sleep research can learn from history. Sleep Health: Journal of the National

Sleep Foundation, 2018 Volume 4, Issue 6, 515 - 518

Ekirch has also published on his website (see here) what he calls ‘fresh’ sources

While it is indeed possible to find numerous examples of the phrase ‘first sleep’ in the literature, an extensive

reading of the original sources given by Ekirch shows there are significant problems with the idea of ‘segmented

sleep’. I have identified 7 major problems for the hypothesis that, to quote Ekirch, “Until the close of the early

modern era, Western Europeans on most evenings experienced two major intervals of sleep bridged by up to an

hour or more of quiet wakefulness“ and that this mode of sleeping was “the predominant pattern of sleep before the

Industrial Revolution”:-

1.

The absence of descriptions in the literature of behaviour actually resembling Ekirch’s proposed ‘segmented

sleep’

2.

The scarcity of the phrase ‘second sleep’ and its absence in almost all other languages in which the phrase ‘first

sleep’ occurs.

3.

The absence of descriptions, or names in any language, of the hypothesised intervening period of wakefulness.

4.

The existence in a number of cultures of ‘third sleep’

5.

The fact that the vast majority of examples of ‘first sleep’ relate to people being ‘in’ or ‘awakened from’ their

‘first sleep’ not awaking after their ‘first sleep’ as Ekirch contends.

6.

The fact that examples of ‘first sleep’ occur at various times of the night and even during the day.

7.

The lack of any scientific evidence of ‘segmented sleep’ in people living under real-life ‘pre-industrial’

conditions.

The tendency has always been strong to believe that whatever received a name must be

an entity or being, having an independent existence of its own - John Stuart Mill

The idea of pre-industrial segmented sleep that Ekirch presents is I believe a classic case of reification, (O.E.D. The

making of something abstract into something more concrete or real; the action of regarding or treating an idea,

concept, etc., as if having material existence). Ekirch has found a number of examples of the use of a phrase, ‘first

sleep’ and from that inferred an entity, ‘segmented sleep’. This I believe is wholly mistaken.

From an unprejudiced reading of the literature it is clear that there are a number of different meanings for ‘first

sleep’ dependent on context.

•

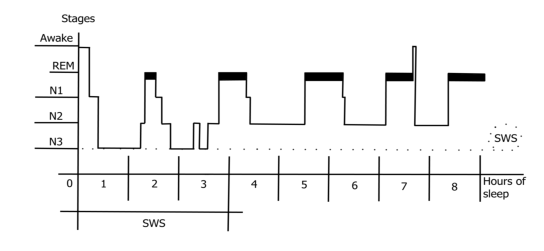

First part of sleep during the night comprising the period spent mainly in deep Slow Wave Sleep (SWS) or

‘complete sleep’ as Robert Macnish in his Philosophy of Sleep 1830 (here) described it

Sleep exists in two states; in the complete and incomplete. The former is characterized by a torpor of the

various organs which compose the brain, and by that of the external senses and voluntary motion.

Incomplete sleep, or dreaming, is the active state of one or more of the cerebral organs, while the remainder

are in repose : the senses and the volition being either suspended or in action according to the

circumstances of the case. Complete sleep is a temporary metaphysical death, though not an organic one —

the heart and lungs performing their offices with their accustomed regularity under the control of the

involuntary muscles.

or ‘core sleep’ as Horne once described it (Why we sleep: the functions of sleep in humans and other mammals

1988). This usage explains why many of the sources used by Ekirch talk about being woken ‘in’ or ‘from’ their

‘first sleep’

‘

•

The initial episode of sleep during the night. This would then mean that any subsequent episode of sleep,

whenever it occurred and of whatever duration, would thus be termed ‘second sleep’. This usage explains the

term used for the short sleep following early rising and also explains the existence of the phrase ‘third sleep’

•

The first sleep/night in a specific place.

•

First sleep as conceptualised by Ekirch, however as I have shown Ekirch provides little actual evidence of this

use.

The importance of context is well illustrated by the following example, which clearly has absolutely nothing to do

with segmented sleep, despite twice using the phrase ‘first sleep’

What a comfort it is, O Saviour, that thou art the first-fruits of them that sleep! Those, that die in thee, do but

sleep. Thou saidst so once of thy Lazarus, and mayest say so of him again: he doth but sleep still. His first

sleep was but short; this latter, though longer, is no less true: out of which, he shall no less surely awake, at

thy second call; than he did before, at thy first. His first sleep and waking was singular; this latter is the same

with ours : we all lie down in our bed of earth, as sure to wake, as ever we can be to shut our eyes. (Works Of

The Right Reverend Father In God, Joseph Hall, D.D. Successively Bishop Of Exeter And Norwich : Now First

Collected. With Some Account Of His Life And Sufferings, Written By Himself. Vol VI.— Devotional Works.

London 1808 here)

Similarly there are clearly different meanings to the phrase ‘second sleep’

•

An episode of sleep occurring sometime after a initial period of sleep

•

Second part of sleep during the night comprising the period spent mainly in REM and stage N2 sleep,

‘incomplete sleep’ as Robert Macnish described it or ‘optional sleep’ as Horne once described it.

•

Second sleep as conceptualised by Ekirch, however as I have shown Ekirch provides no actual evidence of this

meaning

There is also a scientific rationale for waking up, often in dream, at the end of ‘first sleep’ leading to Ekirch to

hypothesise a period of intervening wakefulness. As Torbjorn Akerstedt et al in their paper Awakening from sleep

(Sleep Medicine Reviews, Vol. 6, No. 4, pp 267-286, 2002 here) say “Human subjects awake preferentially at the end

of REM sleep”

What is vitally important is the context the phrase is used, not the mere existence of the phrase. Ekirch appears

blind to the obvious differences in the use of the phrase and indeed seems to wilfully ignore it, as in his discussion

of the existence of ‘first sleep’ in French, Italian and Latin (see footnotes 66, 67, 68 of the first paper) where he

seems to be merely counting the number of occurrences of the phrase without any regards to the context that the

phrase might have been used (I have no proficiency in these languages and so am unable to judge the context). So,

while the appropriate phrase no doubt exists the translation/interpretation is highly dependent on the context hence

the use of ‘first sleep’ to describe a sleep occurring in the middle of the day.

While Ekirch used his first paper set out his theory of ‘segmented sleep’, Ekirch in his second paper broadens his

horizons and ventures into science and more worrying medicine. He offers a number of statements in order to

persuade the reader that ‘segmented sleep’ somehow, over a very short period of time, morphed into consolidated

sleep. Furthermore Ekirch suggests that the modern sleep disorder, middle of the night insomnia, is actually a

throwback to the predominant style of pre-industrial sleep, and is thus, in his view, entirely natural.

I wish to present a far more plausible alternative hypothesis that I believe fully explains the evidence found in the

literature and requires no unsupported assumptions to be made

‘Segmented sleep’ can be fully explained by what Ekirch calls Middle Of The Night insomnia.

Given the fact that the word ‘insomnia’ was not in use till late 1800’s, a different lexicon must have had to be used

to phenomena and this I contend included the use of the phrases ‘first’ and ‘second’ sleep. This explanation

accounts for the paucity of actual descriptions of ‘segmented sleep’, as hypothesised by Ekirch, in the literature, as it

is a condition suffered by a few, rather that the predominant mode of sleep in pre-industrial times. This explanation

also accounts for the fact that there is not a word/phrase for the intervening period of wake, because it was not in

fact a ‘thing’, in the same way that there is no current word/phrase specifically for the period of wake experience

during middle of the night insomnia.

So rather than being the natural way of sleeping, descriptions of ‘segmented sleep’ are merely historical descriptions

of fragmented sleep, disturbed sleep, normal nocturnal awakenings during REM sleep and/or what Ekirch calls

Middle of the Night insomnia (or more accurately ‘difficulty maintaining sleep’, International Classification of Sleep

Disorders 3rd edition).

The fact that the speculations of an historian has influenced the thinking of he clinicians and scientists who have

uncritically and unquestioningly accepted the myth of ‘segmented sleep’ and may have affected the treatment and

lives of patients suffering from insomnia is in my opinion irresponsible. To suggest to a patient with middle of the

night insomnia that their disturbed sleep sleep is somehow ‘natural’ and that they should not attempt to remedy it

is, in my humble opinion, misguided in the extreme.

© Dr. Neil Stanley 2013-2026